Knowledge as Power

The Umayyads, like their ancestors and rivals, recognized that education and knowledge were important tools for social cohesion and political influence. Umayyad caliphs were expected to be highly educated in a variety of disciplines, particularly theology, with special attention to the Qurʼan, Arab grammar, poetry, and Islamic law. Education was a mark of status and prestige. The so-called biographical dictionaries that began to be composed at this time include the careers of literally hundreds of Andalusi Muslim scholars (the ulama), many of whom were in charge of teaching students. The Umayyads also boasted of their capacity to attract scholars, poets, and musicians from all over the medieval world, thereby increasing the capital’s reputation vis-à-vis their rivals.

Madinat al-Zahra became a highly intellectual center, leading to the establishment of courtly intellectualism but also a wider interest in learning across al-Andalus. Poets composed epics that were performed for the delight of the court. In the palace courtyards, astronomers studied the movement of celestial bodies and astrologers interpreted their observations to advise the caliph on state governance. Physicians drew on several sources for the prescription of medical remedies, and engineers developed sophisticated aquaculture to irrigate fields and provide water for the palace gardens. Much of this knowledge was recorded and housed in the great library of caliph al-Hakam II at Córdoba. This vast collection of books was managed by librarians who acquired Greek and Latin scholarly texts and transcribed them into Arabic, adding “the wisdom of the ancients” to the burgeoning works of medieval writers. The palace library also inspired the creation of private book collections and public libraries across al-Andalus, and bookshops could be found in many city markets. The caliphs even provided public teachers of the Qurʼan to share this knowledge, at no cost, with the wider population of al-Andalus.

The Court of the Clocks

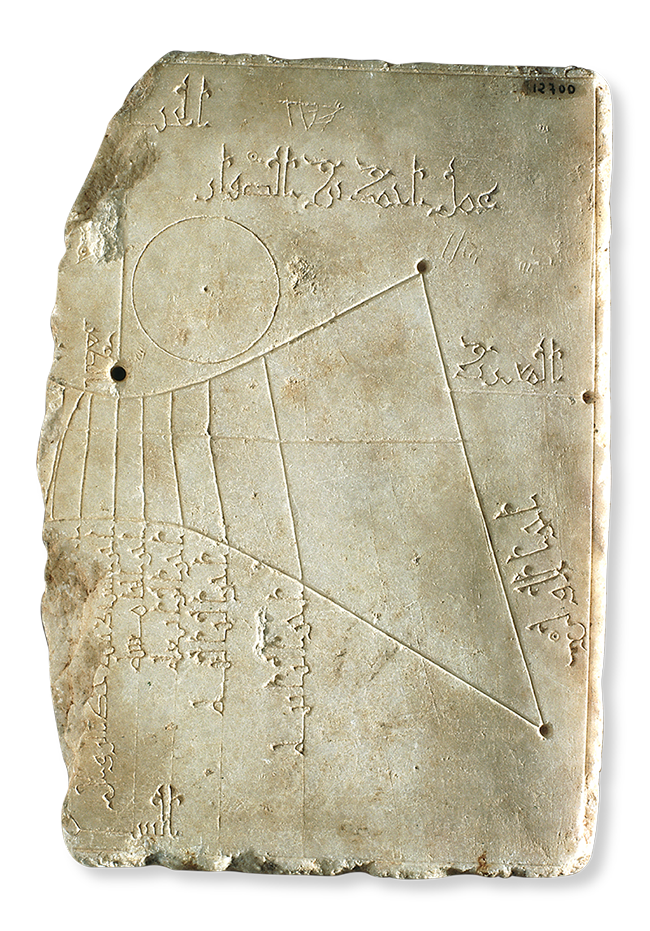

The Court of the Clocks, an open courtyard near the Salón Rico, was a place of scientific discovery. Sundials found in the courtyard can be related to the works of astronomers who were particularly interested in ascertaining the daily times for prayer.

Roman spolia (repurposed art and objects) such as statuary and sarcophagi have also been found here. It has been suggested that the reuse of classical imagery at this particular spot was intended to elevate the intellectual nature of the space with representations of heroes and philosophers from antiquity.

Keeping Time

Sundials were essential tools for timekeeping in the Islamic world, particularly for the timing of the five daily prayers prescribed by Allah and relayed by the Prophet Muhammad. By observing the shadow of the needle on a horizontal table marked with the temporal hours of the day, it is possible to tell the time of day. While not entirely accurate, the production of sundials requires a sophisticated knowledge of mathematics.

These marble sundials mark the hours of the day (as straight lines radiating from the needle), which are named in incised kufic script. Prayer times are also marked, as can be seen in one of the sundials by zigzag lines between the hour lines that mark the start of zuhr, the noon prayers, and the start and end of al-asr, the afternoon prayers. This sundial also has hour lines for the winter and summer solstices as well as a directional marking of the qiblah, the direction of prayer toward Mecca. The other sundial has similar features but also a circle near the needle hole that marked the needle’s height in case it needed to be replaced.

Astrolabes

Astrolabes were portable models of the heavens used for timekeeping and consisted of three main parts. The mater is the main body of the astrolabe and has engraved hours of the day around the edge, called the limb. The plate is the circular disk placed inside the mater; it is a two-dimensional rendering of the three-dimensional hemispherical sky that we see when we look up at the heavens. On top of the plate is the rete, or star net, a metal frame that marks the positions of particular stars and the annual path of the sun. On this brass astrolabe the rete has markers for thirty-three stars, six of which are indicated by the beaks of stylized birds.

This astrolabe was made by the eminent astronomer Hamid Ibn al-Khidr al-Khujandi at the court of the Buyid ruler Fakhr al-Dawla (977–997 CE/366–387 AH) in southern Iran and Iraq, as indicated by an inscription on its back. Once they had been adopted in al-Andalus, astrolabes quickly spread in western Europe in the tenth century, where they became one of the most popular timekeeping devices in the medieval world. Astrolabes were also used for teaching elementary astronomy and for medical astrology, as physicians believed the position of celestial bodies had an important influence on the human condition.

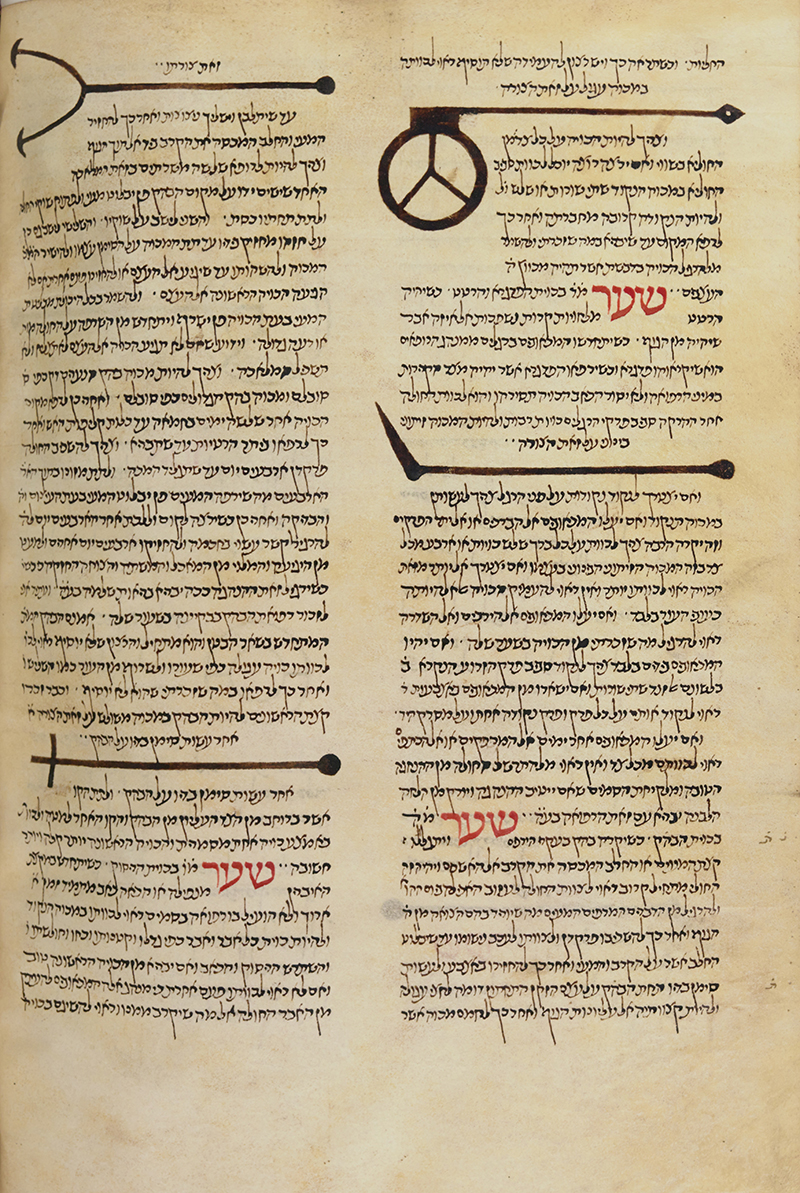

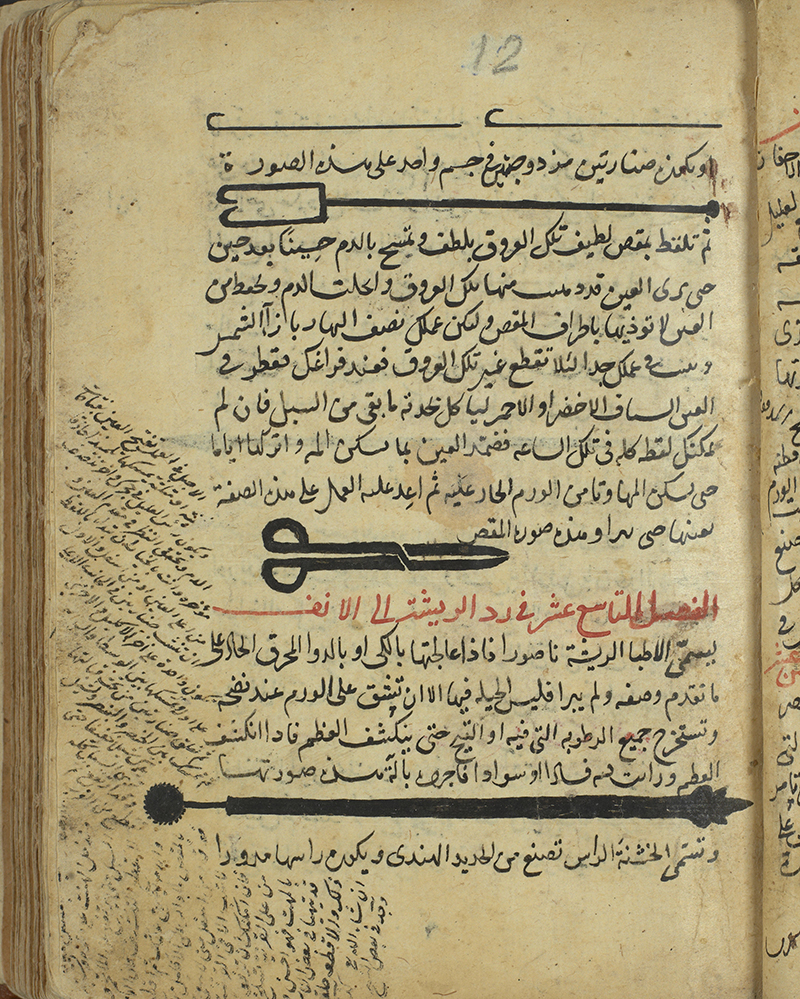

Kitab al-Tasrif Manuscript

Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbas al-Zahrawi was a physician at Madinat al-Zahra who authored an encyclopedic medical handbook titled Kitab al-Tasrif (The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge). His text is arranged into thirty chapters that cover different topics such as anatomy, ophthalmology, dentistry, pharmacology, and diet and nutrition. The most famous chapter is his treatise on surgery, which not only goes into detail about surgical practices but is wonderfully illustrated with drawings of medical instruments he used in his practice. The pages above feature tools for eye and nose surgery, as well as tooth removal. The Kitab al-Tasrif and many other Arabic medical handbooks were translated into Latin and subsequently became influential works in the medical practices of the European Christian kingdoms.