Dining with the Caliph

Cooking and eating were considered art forms in the courts of the Umayyads, Abbasids, and Fatimids, with gastronomy being a marker of status and high culture. During the tenth century CE, some of the earliest Arabic cookbooks were collated from courtly recipes such as the Abbasid Kitab al-tabikh (The Book of Dishes). These cookbooks reveal a variety of regional dishes and fusions of foods and ingredients from across the Islamic caliphates. In al-Andalus, the cookbook Fidalat al-khiwan fi Tayyibat al-Ta’am wa-l-Alwan (Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghreb) comprised recipes that drew on dishes from the Maghreb (Northeast Africa), including flatbreads topped with meat and eggs, rich stews topped with eggplant, and distinct Andalusian confections such as hot honey and cheese pastries (mujabbanat). These unique culinary combinations and innovations characterized not only the sophisticated palettes of the Umayyad court, but also the intercultural cuisine of Andalusian society at large.

Court cuisine was accompanied by a taste for richly decorated glazed tableware that transformed dining into a spectacle. The elegant shapes of ceramics from Madinat al-Zahra attest that eating, too, was an art form, with invitations to the caliph’s table as marks of prestige. The distinctive Umayyad glazed green and manganese bowls and dishes were made especially deep and wide, ideal for generous servings as befit the royal table. The central images on these vessels of animals such as stags, peacocks, and horses were playfully revealed over the course of a meal, making them whimsical elements of the dining experience. However, many ceramics were also decorated with Arabic calligraphy proclaiming the word al-mulk (power), underlining that eating was not only a sumptuous affair, but a political ceremony as well.

Dish with Solomon's Knot Motif

The potters at Madinat al-Zahra developed a distinctive decorative style for the green and manganese pottery used at the royal table, with a preference for images of animals, geometric designs, and Arabic kufic calligraphy. The center of this dish features the “Solomon’s knot” motif, formed by two interlacing loops that intersect perpendicularly and interweave over one another at four points. This motif was common in late Roman mosaics and Persian decorations, and it gained particular significance in medieval Jewish and Islamic imagery as a symbol of the wisdom of the legendary Biblical king Solomon. Islamic archaeologists have suggested that the motif may also be symbolic of the rivers or heavens described in the Qur’an.

While unglazed pottery was used for cooking and serving food, it had to be replaced after a single use. This was because the porous surfaces absorbed foodstuffs and subsequently putrefied, making them harmful for human consumption even after vigorous washing. This unglazed painted jug would have had a short use-life compared to glazed pottery, which could be used multiple times without concern. However, it was still highly decorative with an elegant shape, pseudo-Arabic kufic script, and a repeating pattern of white swirls along its body.

The deep honey and green tinges of this juglet are characteristic of Umayyad amber-glazed ware. These colors were achieved through the addition of iron oxides and copper to the glaze, producing an organic, mottled effect. The dark-brown manganese glaze splashed on the surface might appear careless, but it provides an expressive flare. The colors of the Umayyad honey-glazed ware likely mimicked the golden lustrewares of the Abbasids, which became widely popular across the medieval world.

The palace of Madinat al-Zahra was also home to some of the service and security personnel, who used portable stoves like this one for cooking and keeping dishes warm. An opening at the base of the stove allowed the fire to be tended while the holes on the stove allowed a constant flow of air and vents for smoke. The globular cooking pot that sat on top would have been ideal for cooking dishes such as thar’id—stewed vegetables and meat served on a crisped thin bread that becomes soggy with broth. Thar’id was a beloved dish in al-Andalus and many other parts of the Islamic world, where it was popularly considered to be the favorite dish of the Prophet Muhammad. It is still widely eaten today as a traditional part of the evening fast-breaking meal (iftar) during Ramadan.

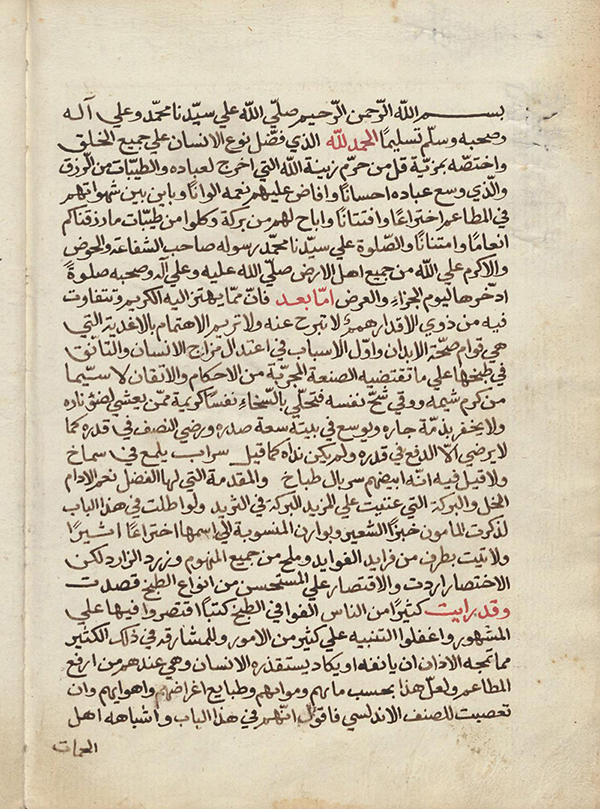

The thirteenth-century-CE Andalusian scholar and poet Ibn Razin al-Tujibi wrote a treatise on cuisine titled Fidalat al-khiwan fi Tayyibat al-Ta’am wa-l-Alwan, or “Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghreb.” This cookbook, of which only three later copies have survived, features a wide array of Anadalusian dishes that may have been popular during the time of the Umayyads. Ibn Razin mentions that many of these dishes were his own creations, while others were delightful meals for special occasions. These included savory dishes of couscous, flatbreads, and stews made with vegetables and meats such as beef, pork, chicken, tuna, and even land snails and locusts. Sweet dishes included candies, cakes, and pastries made with honey, sweet cheeses, and crops introduced to the peninsula including sugarcane, oranges, bananas, dates, and pomegranates. Many of these foods could be purchased at markets (suqs), which were tightly monitored by inspectors for cleanliness and high standards.