Gifts Fit for a King

Luxury goods such as precious fountain spouts and perfume bottles, ivory pyxides, glazed ceramics, and even gold coinage were not intended to be enjoyed exclusively by the caliph and his royal court. Many were specifically made as gifts for both rivals and allies across the medieval world. The presentation of gifts was an important means of establishing political and social relationships between rulers, and helped to shape relationships with friends and allies. Diplomats serving the Umayyad caliphs traveled to the royal courts of the Christian kingdoms of Iberia, Europe, and the Byzantine Empire, presenting magnificent works from the royal workshops at Madinat al-Zahra. Luxury items were also sent to rulers and tribal chieftains in North Africa whose alliance was sought in order to counteract Fatimid influence. In return, the Umayyad caliphs received gifts such as manuscripts, rare animals, or raw materials that were brought back to Madinat al-Zahra and displayed as testament to the far-reaching influence and power of the Umayyads.

During the tenth century CE, diplomacy through the presentation of gifts led to the creation of a wide community of rulers, courtiers, and elites who shared the taste for an opulent lifestyle. The decoration of gifted objects reflected the emergence of broader international preferences and visual vocabularies in the decorative arts, including a particular interest in intricate and densely packed designs found in textiles, metalwork, pottery, and architecture.

Gifts played a similarly important role in expressing power and fostering relationships within Andalusian society. Viziers were bestowed robes of honor (khil‘a) when they were appointed, officials received lavish rewards upon completion of important assignments, and prominent poets were endowed with material tokens of praise. In this domestic scenario, gifts of precious objects and exotic materials from the royal workshops became the caliphate’s preferred tools to maintain cooperative relationships with these audiences.

The Charilla Treasure

Hoards, often termed “treasures,” are collections of objects, often made of valuable materials, that have been hidden for safekeeping. People hide objects for a variety of reasons, including collecting things to trade, concealing valuables at times of turmoil, protecting cherished heirlooms, and even secreting stolen objects. The objects in this case were part of a hoard found in 1977 by a local farmer near the city of Alcalá la Real in the municipality of Charilla, and have subsequently been called the “Charilla Treasure.”

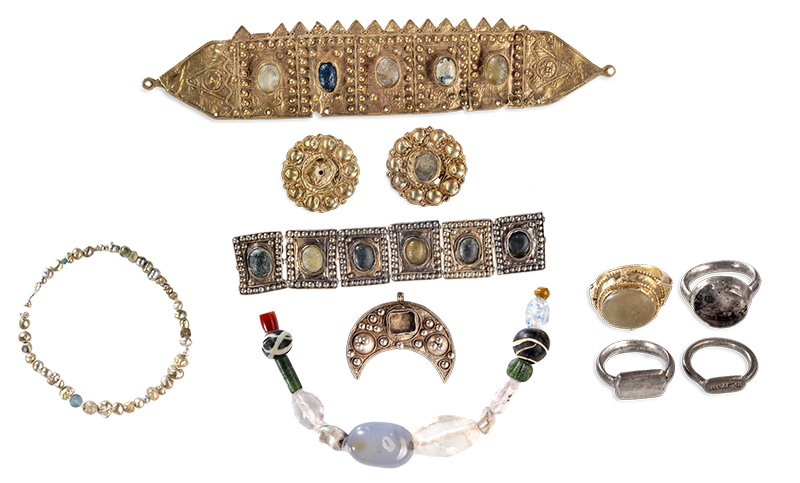

The Charilla Treasure is a collection of some of the finest examples of Umayyad jewelry. The pieces in the hoard include some worn by both men and women: diadems, necklaces, rings, and hairpins. Many of the pieces were likely made in the caliphal workshops, given their fine craftsmanship and valuable materials including silver, gold, semiprecious stones, and pearls. Some may have also been locally made, such as the silver caliphal coins that were perforated to be worn. These could have been stylish fashion statements as well as a means to store wealth for the future. Given their exceptional quality and value, the jewelry of the Charilla hoard likely belonged to a wealthy family who received the objects as gifts from the caliphal workshops. The reason the collection was hidden is unknown, but clearly some sort of danger caused the owners to bury it and they were unable to return or suffered an untimely demise.

Diadem, gold and glass, ISAW no. 102; Hairpins, gold and glass, ISAW nos. 106–7; Choker, gold and glass, ISAW no. 103; Necklace beads, irregular pearls and glass, ISAW no. 132; Stone necklace beads, rock crystal, chalcedony, pearl, carnelian, and glass, ISAW no. 131; Pendant, gold and missing glass, ISAW no. 104; Rings, gold, glass, and silver, ISAW nos. 120–123, all 10th century CE, Museo Provincial de Jaen.

Four dirham coins with perforations, silver, 945–970 CE, Museo Provincial de Jaen, ISAW nos. 142–145.

Textual sources mention that the Byzantine emperor once presented an Umayyad ambassador with the gift of a beautiful and massive green marble basin for Caliph ‘Abd al-Rahman III. The caliph was so delighted by the gift that he had the royal workshops fashion gold fountain spouts encrusted with jewels in the shape of various animals, transforming the basin into a spectacular fountain for the palace gardens. This bronze spout in the shape of a deer probably came from one of the many fountains that were scattered across the palace and inspired that account. Its elegant body is covered in an etched pattern of scrolling vines, and the bronze would originally have been a golden color that sparkled in the palace gardens.

Pyxides were used as containers for jewelry and perfumes, and commonly made by sawing and hollowing out a section of elephant tusk. The dense, symmetrical, repeating patterns on this example testify to the skill of the ivory carvers at Madinat al-Zahra. Scrolling vines, flowers, and palmettes exhibit the characteristic arabesque and vegetal patterns of Islamic art and are paralleled on many of the carved wall reliefs and column capitals from the palace. The mirrored pairs of parrots, gazelles, and lions provide a sense of whimsy and may also allude to the fauna of the Umayyads’ ancestral home in Syria.

These silver perfume bottles were found in two different hoards, and are fine examples of the types of prestigious metal vessels produced at the Umayyad workshops. Both bottles have similar flowing meanders across the body that highlight their globular shape. One of the bottles (left) has more ornate decoration, with stylized palmettes and vegetal designs. Its domed lid, attached to the bottle by a chain, and horseshoe-shaped arches and columns encircling the neck give the appearance of an ornate tower.